A strange error code suddenly pops up in your access logs from NGINX: 499. Not a classic 4xx or 5xx, but something in between. Not a standard part of the HTTP protocol. And yet really a status code.

What's going on?

The 499 status code means that the client, meaning the browser, script or application, terminated the connection itself before the server could provide a response. The server was processing the request, but did not get a chance to respond. With slow websites, this can happen more often, making a switch to Cloud Hosting or to Fast WordPress Hosting sometimes provides the solution.

Why does http 499 exist in the first place?

This code is not defined in the official HTTP specification. Therefore, you won't find it in RFCs or standard developer documentation. HTTP 499 was invented by NGINX specifically to log situations where the server is not at fault.

Imagine this: a user clicks on a link, realizes it was the wrong one and presses "stop. Or an app disconnects because a timeout has been reached. From the server's perspective, it looks like the request just dropped. So NGINX logs that as 499 http status code, a client pulling the plug itself.

How does a 499 error message occur?

There are several scenarios in which you may encounter this code:

- A user closes the browser or clicks away while a page is loading.

- A frontend application cancels a fetch call with AbortController.

- A mobile connection drops out halfway through a request.

- An API consumer uses a short client timeout that expires before the server can reply.

- A monitoring or scraping tool fails due to throttling or rate limiting.

In all these cases, the server remains active, but its work is cut off early.

Where do you see this error?

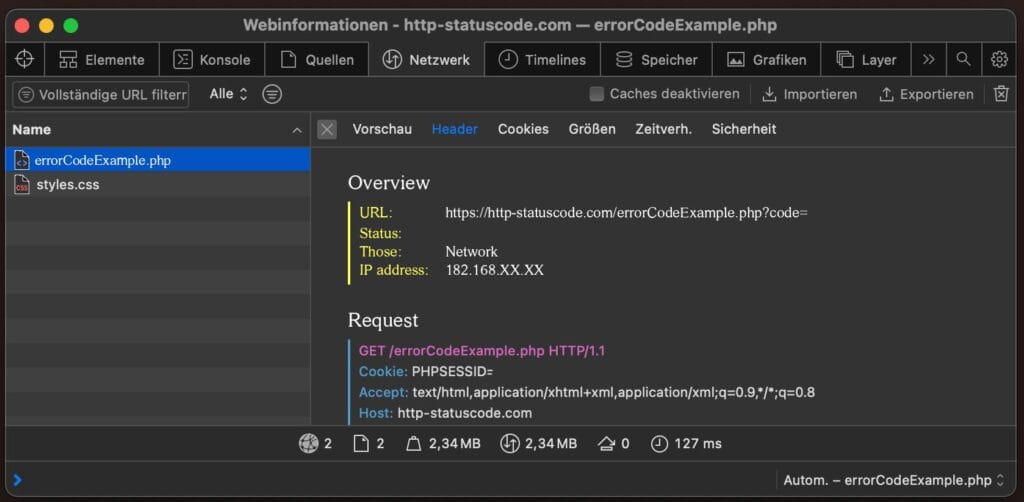

You will not see status code 499 in the browser or on the frontend. It is purely a log message registered by NGINX on the server side. So you will find it in log files like:

GET /api/data HTTP/1.1″ 499 0 "-" "Mozilla/5.0"

This status can also pop up in tools like Screaming Frog, especially if you are crawling through a proxy and the server takes too long to respond while fetching pages.

Is a 499 serious?

As such, no. An occasional 499 http error is quite normal, especially with interactive applications or mobile users. But if you encounter this status frequently in your logs, it may indicate underlying problems.

Possible causes are:

- Endpoints that are structurally slow to respond

- Front-end logic that cancels requests too quickly

- Proxy or load balancer settings that disconnect early

- Users dropping out during load times

In those cases, you have to look further: how long do your requests really take? What is the ratio of 200's to 499's on the same route? Are there peaks at certain times or devices?

What can you do when there are a lot of 499 errors?

Start with the basics:

- Measure your load times with APM tools (such as New Relic, Datadog or Elastic APM).

- Check if certain routes consistently take longer than the set client timeout.

- If necessary, adjust the timeout of your clients or reverse proxy.

- Make sure your frontend does not cancel too aggressively when navigating or under time pressure.

- Consider caching or preloading if responses are heavy.

Often it is not a bug, but a mismatch in expectations: the client wants an answer faster than the server can deliver. The solution then lies in performance tuning or in expectation management (for example, with loaders or retry logic).

Summary

The 499 status code is a silent break in communication. The server was talking, but the other hung up. No crash, no broken endpoint, but no successful interaction either.

It's a warning. Not to scare you immediately, but to take seriously if you see them coming back often. Status 499 means: your backend needs to be faster or your client needs to be quieter.

If you know where things are going wrong, you can make better choices. Whether it's infrastructure, API design or front-end behavior, http 499 is a signal to pause and consider the rhythm of your communications.